Unlike mellifluous Italian, with its five pure vowels, English is a rhyme-poor language.

If you become a wide reader of English poetry, you’ll soon anticipate certain rhymes.

For example, “love” will often be paired with “prove” or “move.” The linkage is so common that it’s a surprise when “dove” ends a couplet.

Unfortunately for the writers of love poetry, “love” has only a handful of rhymes.

Many other words are similarly stranded.

Thus, it’s a marvel when Alexander Pope, for example, writes rhyming line after line without fillers, each line never forced, but feeling natural and easy. In rhyme-poor English, this is a marvel indeed.

But maybe the poverty of rhymes in English is the language’s great advantage.

A university professor once told me that the lack of rhymes in English is one of the reasons that English poetry is one of the greatest of the world.

The lack of rhymes, he said, forces the imagination into directions it otherwise wouldn’t go.

Wendy Walker, author of the magisterial The Secret Service, would seem to agree. She has contended that working within limitations leads to great literature. In pursuit of new limitations—even if arbitrary—she has experimented with poetry that limits itself to letters without risers (such as h, b, k) and without descenders (such as p, j, g).

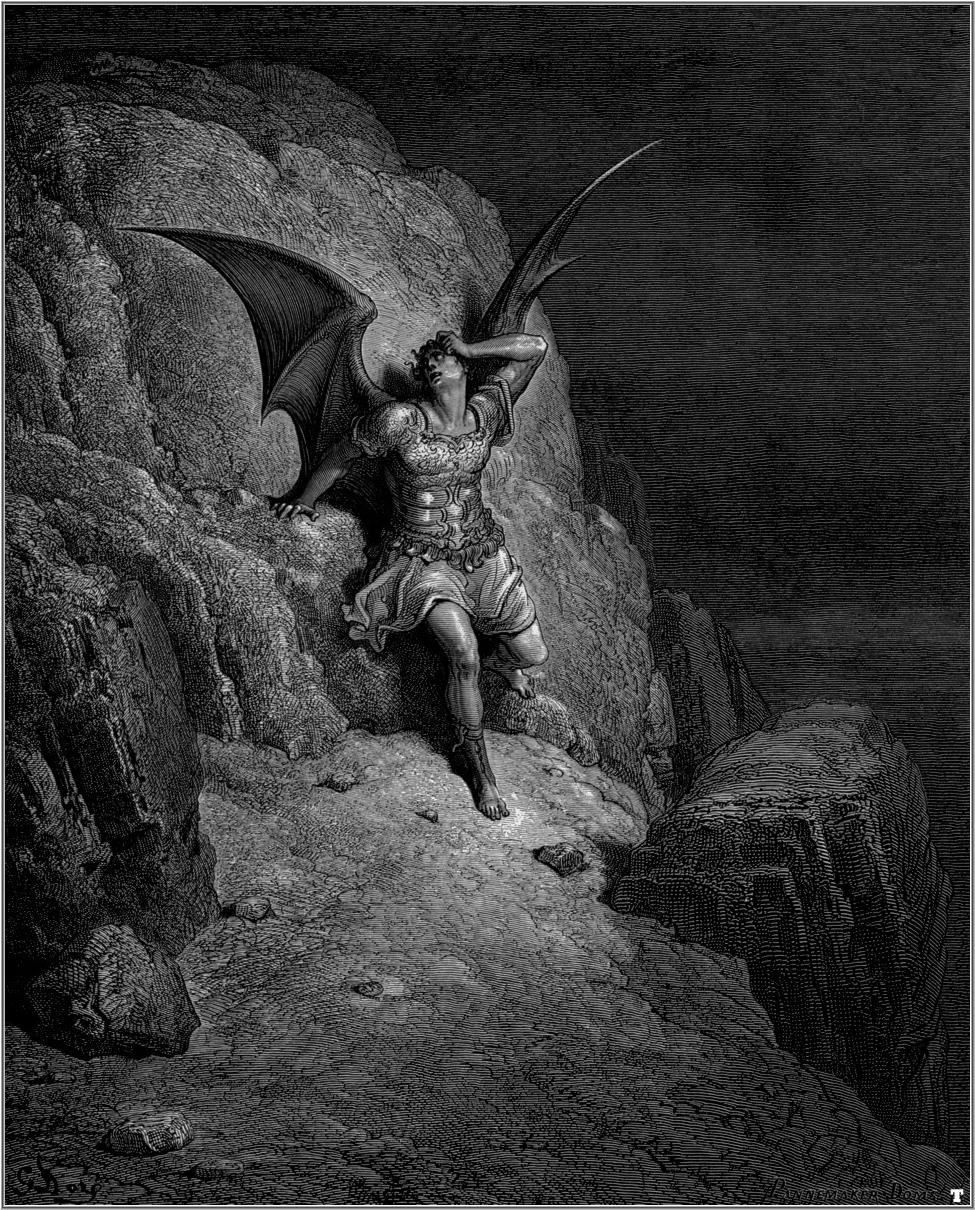

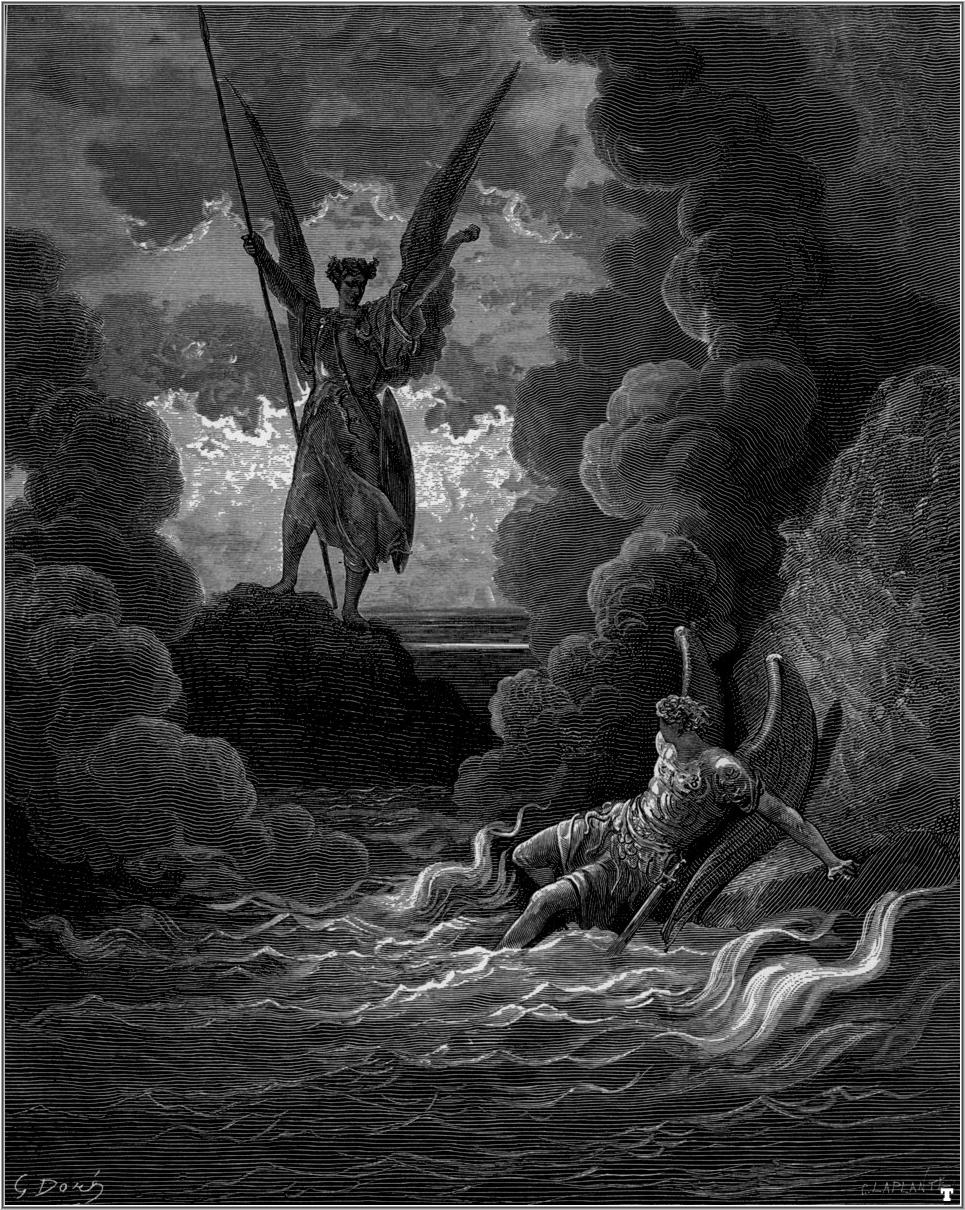

John Milton rejected rhymes for long poems such as Paradise Lost. And yet, Paradise Lost has its own constraints: its iambic pentameter is rarely irregular, and the verbs “to be” and “to have” are minimized almost to absence, thus giving the poem a verbal vigor that is one of its chief gems.

Limitations in language can produce an abundance of riches.

* Orlando Bartro is the author of Toward Two Words, a comical novel about a man who finds yet another woman he never knew, available at Amazon. He is currently writing two new novels and a play.