My mother, Mary O’Brien, celebrated her 96th birthday on Christmas Eve, 2002, which was the last birthday she celebrated.

In her later years, I started interviewing her all the time, trying to find out information about family and friends, but her mind was quite selective in what it was willing to release. My dad drank too much and smoked too much, and that contributed to his death at age 63. Mom remembered that, but all she'd say was, "I always loved him. He always loved you kids. He never left us."

Some years back, I wasn't impressed with that. But the more mothers I meet at book-signings whose husbands no longer are a part of the family I realize that my Dad not leaving us was a plus in our life. I knew that my mother and my father loved me. They had their moles, but they never thought I had any.

"He didn't drive, but he took you kids to a lot of places," she'd say.

"He always went to work," she'd continue. "During the Depression, he didn't have a job for about six or seven years. But he went out every day and knocked on doors, and asked for work. He'd do whatever he could do to make some money. He always brought home some money."

That story has become my personal mantra. I've never been afraid to knock on doors, and ask for work. And I still smile, and think of Mom's story, when I come home with some money.

My father eventually landed a full-time job as a machinist at Mesta Machine Company in West Homestead and remained there for 34 years. He claimed he was usually given the difficult drilling assignments, the ones with the smallest allowance for error. He had dropped out of school in fifth grade and he had to call my mother on the telephone and tell her the numbers on the job assignment and she’d figure out the math for him so he knew exactly where to drill the holes. They were a great team in that regard.

This was always a busy time of the year for both of my parents. My dad went to a lot of parties at this time of year. Most of those parties were held in neighborhood bars and speakeasies. There were 36 bars in a mile-long stretch between Hazelwood Avenue and the Glenwood Bridge in my hometown of Hazelwood. My Dad was familiar with most of them, and ran a tab in a half dozen of them. I delivered newspapers to most of them, from the time I was ten to the time I was 13, so the bar owners knew me, too. I was Dan's son. They treated me well. Orange soda and potato chips on the house, sometimes a hard-boiled egg. They had to have some food in the house according to the bar code.

When my dad cashed his paycheck from Mesta at the Hazelwood Bank at one end of town, he walked, not always steadily, a veritable minefield on his way home. He had to leave a lot of that money at many of those bars to clear his account. My mother never knew how much he'd be turning over to her by the time he reached our door. Sometimes, she acted as if she'd hit the numbers, sometimes she was saddened by the shortfall.

The older I get the more I appreciate my Dad. He was never demanding, never in my face. He never gave me a hard time. He hit me on the backside with his belt twice for smoking at age 9 and at age 13, but I survived and I don’t smoke. That was his gift to me. I hardly ever drink, and I do not touch the hard stuff.

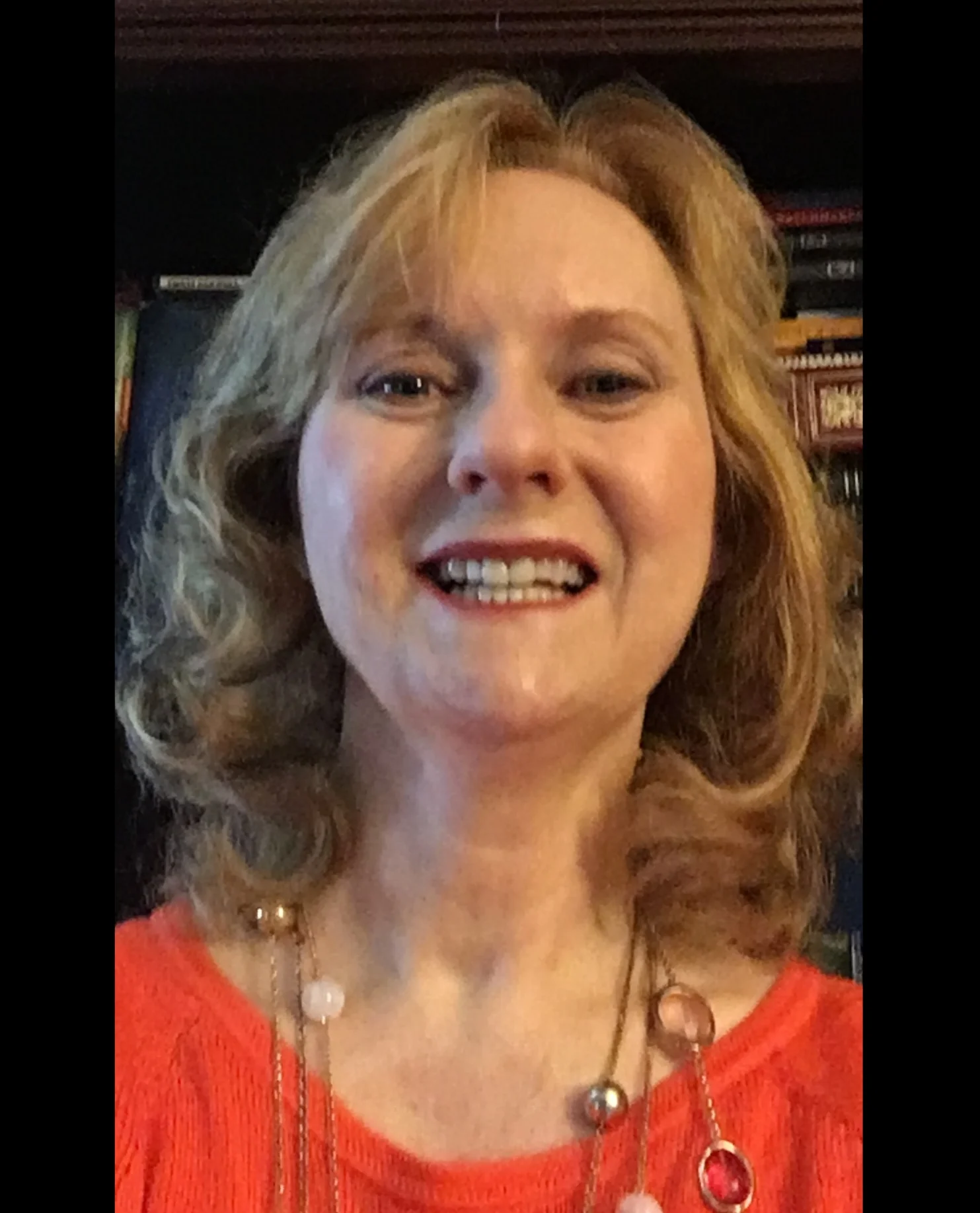

My mother, Mary O’Brien, at age 50 in 1956, was one of the first female clerks in a State Store.

This was a busy time of year for my mother as well. She worked as a sales clerk at the State Store on Second Avenue. My dad and mother were both good workers. This was the busiest time at the State Store. Everybody was buying liquor and wine to celebrate the season. She took pride in being one of the first female clerks in the State Store system.

I met many interesting characters whenever I'd go to the State Store to see my mother. She worked a swing shift, and I'd join her for lunch on the days she worked the early shift. Sometimes I'd have to wait in the back, between the tall rows of whiskey and wine, and I'd read the labels. Many were quite attractive.

Some customers came regularly and were well known. There was "Duffy the Drunk" and "Duffy the Boxer," and a woman with scraggly dishwater gray hair known as "Swing and Sway" for her walking motion. The unkind critics would say she was staggering. The winos would bum money outside the State Store till they had enough money to buy some Tiger Rose.

I met one of my first pro football players, Chuck Cherundolo, who had been a center at Penn State and with the Steelers. He was a wine salesman. So were two local boxing heroes, Fritzie Zivic of Lawrenceville, and Charlie Afif from The Hill. Zivic had been a storied world champion.

Mom and I went to lunch in local restaurants. To me, Isaly's was The Colony or Lemont of Hazelwood. The waitresses all knew my Mom and me. It started a lifetime of my mother and me going to lunch together. "I don't think you and your mother ever see each other that you're not eating," my wife Kathie would say, sarcastically, of course.

It was at this time of year, when I was nine years old, that I asked my mother to buy me a toy printing press, an Ace model, when we were Christmas shopping at the Hazelwood Variety Store. That's how I got started in this business. My mother never turned me down. She always believed in me even when she shouldn't have. She was always my biggest fan.

I missed the mother of my childhood. Her memory wasn't so good anymore. She knew me, most of the time, anyhow. I was her Jimmy, her boy. "You're looking good," she’d say, over and over. "You're as cute as Christmas."

Jim O’Brien has a new book called “From A to Z: A Boxing Memoir from Ali to

Zivic.” His website is www.jimobriensportsauthor.com