This month, we are featuring Carrie Chapman Catt and Ansel Adams, two individuals who worked tirelessly for change.

Catt was a suffragist who was instrumental to the passage of the 19th Amendment.

Ansel Adams was a gifted photographer who used his talents to help promote conservation. During World War II, Catt and Adams stepped out of their comfort zones to bring attention to injustices.

Carrie Chapman Catt was born Carrie Clinton Lane in 1859. She died in 1947 at the age of 88.

From a young age, Catt was interested in science and wanted to become a doctor. After graduating high school, she enrolled at Iowa Agricultural College (now Iowa State University) in Ames, Iowa.

Catt’s father was hesitant to allow his daughter to go to college, but finally relented agreeing to pay only part of her tuition and expenses.

Catt worked her way through school washing dishes, working in the school library, and teaching at rural schools during school breaks.

She was one of only six women in her freshmen class of 27 students.

She joined the Crescent Literary Society and worked to give women equal opportunities at their meetings. Because of Catt, women earned the right to speak in meetings. She started a women’s debate club and advocated for women to be allowed to participate in military drills. Catt graduated in 1880 with a degree in science. She was the only woman in her class to graduate. After graduation, she worked as a law clerk and a teacher. She became the first female superintendent of schools in Mason. Iowa.

In 1885, she married newspaper editor Leo Chapman who fell ill with typhoid fever a year later while looking for a new job and a home for he and Catt in San Francisco. By the time Catt reached California by train, her husband was dead. She was a 27-year-old widow, alone in a strange city, but she remained in San Francisco writing freelance articles and selling newspaper ads. In 1887, when she returned to Iowa, she became actively involved with the Iowa Woman Suffrage Association and National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

She wrote “Zenobia” in 1887 and “The American Sovereign” in 1888. In 1890, she met and married George Catt, a wealthy engineer and alumnus of Iowa State University. George Catt encouraged his wife to remain active in the Women’s Suffrage Movement. She continued to lecture and write. In 1893, she wrote “Subject and Sovereign,” followed by “ Danger to Our Government in 1894. Catt also traveled extensively campaigning for suffrage.

Catt became a leader in the NAWSA and helped strengthen the organization. When Cady Stanton’s controversial book, The Women’s Bible was published many bristled at it’s rejection of biblical stereotypes of women and their roles as inferior passive helpers in a patriarchal society. Catt along with Susan B. Anthony had to distance the organization from Stanton’s book. In 1898, Catt met Mary Church Terrell an African American activist for racial equality and women’s suffrage. Catt and Terrell became lifelong friends. In 1900, Catt succeeded Anthony as president of the NAWSA. She stepped down in 1904 to care for her husband who died the following year.

Racial prejudice reared it’s ugly head in 1903 when Southern delegates were angered that Black women were encouraged and allowed to speak at meetings and form their own chapters. Catt called for unity among all women regardless of skin color.

Catt was re-elected president of the NAWSA in 1915. She increased the size and power of the organization and unveiled her winning plan to finally secure women’s rights to vote in local, state, and federal elections. Her idea was to secure national suffrage by amendment of the U.S. Constitution instead of working state by state.

Her plan had four components:

1. States where women had presidential suffrage would lobby their state legislatures to send resolutions to Congress to support a federal amendment.

2. Women who lived in states where securing suffrage was possible would push for it.

3. Suffragists in most states would advocate for presidential suffrage.

4. Southern states where suffragists met the most resistance would lobby for primary suffrage.

Catt focused on New York state because before 1917, only Western states had passed women’s suffrage. Once New York passed women’s suffrage, the NAWSA had a foothold not only in the West, but also in the North and the East which were more heavily populated than the South.

When Woodrow Wilson went before Congress to request a declaration of war against Germany in 1917, Catt made the controversial decision to support it. The NAWSA had previously opposed war. Her decision made the group seem more patriotic and therefore more acceptable to many Americans. President Wilson threw his support behind the NAWSA in 1918. The suffrage amendment passed the House by one more vote than the required two-thirds majority necessary. It lost by two votes in the Senate. A month later an armistice was declared, and World War I ended.

In February 1919, the women’s suffrage amendment lost by one vote in the Senate, but heavy campaigning by suffragists helped elect more representatives in the House who supported the amendment. When the amendment came up for a vote in the House in May 1919, it passed 304 to 89. In the Senate, it passed by two votes more than the two-thirds majority needed.

Catt led the fight to ratify the 19th Amendment which needed 36 states to vote in favor of ratification. Southern states rushed to vote against the amendment – ten states did. The governors of Connecticut and Vermont refused to call their legislatures into session to vote on the issue. If any of the other states voted no or abstained the amendment would fail. Tennessee narrowly approved the amendment keeping it alive. On August 26, 1920, the 19th Amendment was officially adopted, and 27 million women gained the right to vote. It was the largest single expansion of voting rights in U.S. history.

Catt retired from the NAWSA after establishing the League of Women Voters to encourage women to use their vote and make informed choices,

Catt also worked for international women’s suffrage forming the International Women’s Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) in 1902. It eventually grew to 32 nations strong. Even after her retirement from the NAWSA, Catt remained active in the IWSA.

She opposed Hitler’s treatment of the Jews in the late 1930s and lobbied Washington to accept more Jewish immigrants fleeing persecution. She became the first woman to receive the American Hebrew Medal. It was one of many awards and honors she received during her life and after her death.

Catt’s views on equality and acceptance evolved and became more inclusive as she became more active in the suffrage movement. Her work influenced and inspired countless women and men to look beyond race, religion, nationality, and gender to see all humans as equals. She believed in the power of democracy and working within the system to improve societies around the world.

Sources for this article:

https://www.loc.gov/collections/carrie-chapman-catt-papers/about-this-collection/

Ansel Adams (1902-1984) was born in San Francisco, California. His paternal grandfather founded a lumber business, and Adam’s father later managed the business. Later in life, Adams condemned the family business for damaging so many redwood forests.

Adams did not do well in school. His teachers described him as restless and inattentive. When Adams was 12, his father removed him from school. He was tutored by his father and his Aunt Mary for the next two years.

His father was a great admirer of Ralph Waldo Emerson, and he raised Adams to live a modest life and be guided by a social responsibility to humans and nature.

Twelve-year-old Adams loved music and dreamed of becoming a classical pianist. During this time, He was given his first camera while on a trip to Yosemite National Park. He discovered his love of photography.

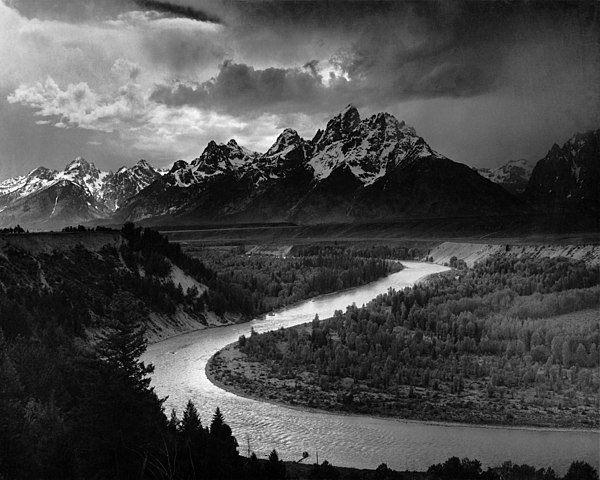

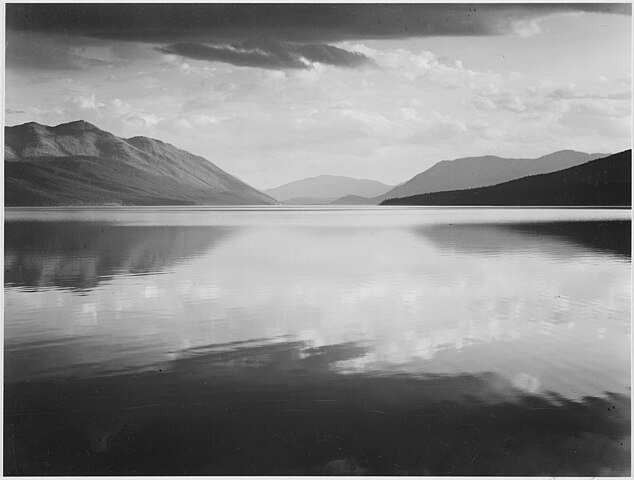

When he was 17, Adams joined the Sierra Club. He remained a member for the rest of his life. During his twenties, he spent the summers hiking, camping, and photographing landscapes. For the rest of the year, he worked on improving his piano playing technique.

In 1921, his first photographs were published and offered for sale.

He married Virginia Best in 1928. Their first child Michael was born in 1933 followed two years later by Anne. Adams worked to improve his photography skills and gained a reputation for excellence among his peers. His photographs helped bring awareness about conservation and the protection of our wilderness.

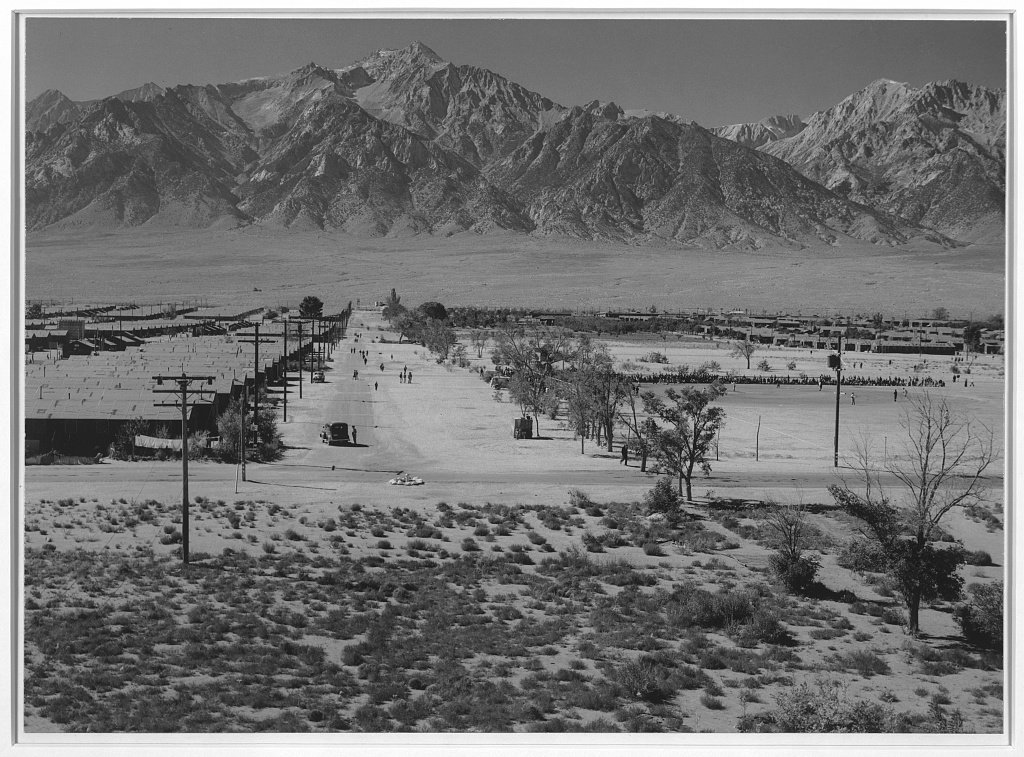

Adams was known for his landscapes, but in 1943, he photographed Japanese who were being interned at the Manzanar War Relocation Center in Owens Valley, California. He become concerned about the injustices being perpetuated on Japanese Americans during World War II after one of his father’s longtime employees was removed from a San Francisco hospital to a facility in Missouri because he was Japanese. Adams had a friend affiliated with the Manzanar Camp and asked permission to photograph some of its detainees. Adams photographs showed people striving to live dignified and productive lives within the camp despite losing their homes, freedom, jobs, and most of their personal belongings simply for being Japanese or Japanese Americans.

The collection of photographs was first featured in a Museum of Modern Art exhibition. It was later published as a book titled Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese Americans. At first the book was considered controversial, and some deemed it unpatriotic and disloyal, but his photographs showed human beings. Adams photographs helped change American opinion about the internment camps and helped show Japanese and Japanese American people in a positive light.

Adams also contributed to the war effort by doing many photographic assignments for the military including photographing secret Japanese installations in the Aleutian Islands.

As Adams grew older, he began to take photographs from a camera mounted atop a tripod on his vehicle instead of making the treacherous mountain hikes of his youth.

Adams received many awards and honors during his brilliant career including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1980 and three Guggenheim Fellowships.

Sources for this article:

https://www.loc.gov/collections/ansel-adams-manzanar/about-this-collection/